The bestselling "adventure" bike in the world is, absurdly, BMW's R1200GS.  I'll grant you: It's comfortable, reasonably robust and divine on the road (100hp+ from a low-mounted boxer doesn't hurt). But bear in mind the compromises inherent to motorcycling: There's no such thing as a delicious low-carb lunch, and this beast is a fat slice of cookie dough cheesecake. It weighs over 500lbs and costs $16,000 and up. BMW also does an "Adventure" version that comes with some accessories like a bigger tank, a heftier price and correspondingly increased pudge.

I'll grant you: It's comfortable, reasonably robust and divine on the road (100hp+ from a low-mounted boxer doesn't hurt). But bear in mind the compromises inherent to motorcycling: There's no such thing as a delicious low-carb lunch, and this beast is a fat slice of cookie dough cheesecake. It weighs over 500lbs and costs $16,000 and up. BMW also does an "Adventure" version that comes with some accessories like a bigger tank, a heftier price and correspondingly increased pudge.

That's not a motorcycle, that's a Civic with a side stand. Why the heck does anyone buy BMW's cash cow to go off-road?

3 reasons, as far as I can figure:

1. BMW's marketing tries their very best to make the GS look like a dirtbike with a windscreen. ("Travel enduro" that has an "enduro pro" electronic configuration - give me a break)

2. GSs starred in Long Way Round, a TV documentary series with Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman, where they rode around the world (and then to the southern tip of Africa in the follow-up, Long Way Down)

3. Partially as a result of 1 and 2, there is a widely held but naive belief that a two-wheeled machine weighing 500lbs will make it through even mildly gnarly terrain without extreme physical exertion on the part of the rider.

Following the GS's surge in popularity in the mid-2000s (McGregor and Boorman likely had something to do with that), other companies were quick to jump on the high-margin bandwagon. The R1200GS now has esteemed company in the 1000cc+ furniture class. For example:

The stupefyingly overweight but charismatic Triumph Explorer 1200 -

Ducati's herniatingly fast and seductively sexy sportbike on stilts, the Multistrada 1200:

Yamaha's bonkers Super Ténéré (which used to mean "desert" or "wilderness" but now means "where is the nearest paved road please")

The quirky and unashamedly road-hugging Moto Guzzi Stelvio:

And the biggest pants-on-fire pretender of them all (albeit the most convincingly rugged), the KTM 1190 Adventure:

Riding a 500lbs+ bike off-road is possible (and highly marketable) - it just takes serious skill and stamina.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NpCubYprqFQ

So what's the problem with all these monstrositycycles?

Even if you're Chris Birch and you manage to keep the rubber side down most of the time, the occasional tip-over during your journey through the swamps could present a trip-ending catastrophe, leaving you and your Bavarian sofa stranded in three feet of mud. A rider on a lighter bike would simply pick up, winch out if necessary and move on.

Say you're a bodybuilder and you have no problem setting a 500lbs bike upright on a sloppy muddy slope, ten times in a day - problem solved? No. When that much mass falls over, it's storing kinetic and potential energy that gets transferred back to the ground, sometimes via the bike's hard parts (levers, shrouds, gas tank, handlebars - which then break) and sometimes via your frail body (which also breaks). Trust me when I say you'd much rather have a slim 300lb bike fall on you instead of a bulbous 500lb one. (if you don't trust me, trust Walter Colebatch, who knows more about ADV riding than any of us)

So - what are the alternatives? I'll get to that as part of another post, but in the meantime, keep this rule of thumb in mind: Never ride a bike a bike off-road if you can't pick it up. On the contrary - if you're riding ADV, ride the bike that would be your pick on the worst section of your trip.

You think gear is expensive? It's cheap compared to the alternative. Motorcyclists should spend their money on good gear they love wearing, and put the remainder toward whatever motorcycle they can get ahold of - not the other way around.

The number of helmetless motorcycle riders in Texas surprises me. But what astounds me more is how many otherwise reasonable people think a helmet alone is remotely adequate protection when riding on- or off-road at any speed faster than a drunk turtle. Your head is important, but the rest of your soft, fleshy self is very much worth protecting on every ride - and I'll get into the why and how in this post.

Most motorcycle injuries fall into three broad, self-descriptive categories: Abrasion, impact and hyperextension (and ego, but you'll get over yourself). Abrasion means grinding against a rough surface (usually a road); impact injuries occur when the rider is hit by something at high speed and/or pressure; hyperextension is when a joint is forced to extend past its intended angle

The mix of the injuries in a given wreck depends on many factors. Principally: Collision speed/angle (duh), road surface and protective gear used.

If you ride on pavement, the first thing to know is every crash on the road involves abrasion. The second thing to know: Abrasion sucks. Pavement is extremely grippy and tough, textured like a grinder wheel. You liked the grip a few seconds ago, but now you're flying through the air and you have more complex feelings:

Even at residential area speeds, the road will shred normal jeans, then it will grind flesh to the bone. "Road rash" will land you in a hospital bed in excruciating pain, while a nurse cleans your skin and changes your bandages every day for weeks.

The good news is you can almost completely eliminate the worst of abrasion injuries by wearing suitable protection. This gear usually takes the form of reinforced pants and jackets or one-piece suits (in addition to other items which we'll get to later). The ideal material to protect against road abrasion is leather - it usually slides without tumbling or tearing. Leather has downsides though: It's expensive, it doesn't breathe well, it requires regular special care and it can get gross in the rain. Some riders wear textile/mesh or Kevlar instead. While textile doesn't slide as gracefully as leather, it offers great protection at road-legal speeds and in mesh form, it's very breathable.

Motorcycle-specific jackets and pants often have special pockets for pads and a back protector. If you're riding hard off-road you may choose full-fledged armor held together by mesh or elastic; it breathes even better than a textile jacket and offers superior impact protection, albeit at the expense of abrasion protection. You could even go full Robocop and wear road-focused textile over your armor.

So that's abrasion covered (no pun intended). What about impacts?

As a motorcyclist, there is no way to fully protect yourself from impacts - you can only distribute force over as large an area as possible and hope for the best. So let's talk helmets.

There's an old saying, "only buy a hundred-dollar helmet if you got a hundred-dollar head", implying riders should spend--many hundreds? thousands?--on helmets. Ben Moore beat me to empirically dispelling this myth using public data from the UK's SHARP helmet safety rating program. Ben's findings in a nutshell: Expensive helmets are usually more comfortable, more aerodynamic, equipped with coms and other electronics and/or made with lightweight materials, but there is little or no evidence they offer better protection than a sturdy DOT certified helmet you can pick up for <$150 almost anywhere. As long as a DOT helmet is not expired (yep, they expire when the shell deteriorates), it can save you just like a $800 race replica can.

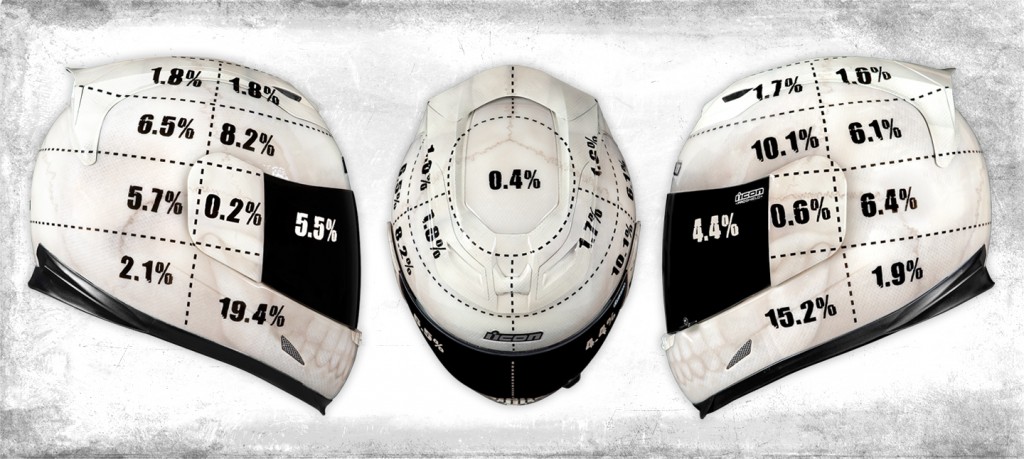

Price may not matter much for safety, but coverage does. A full-face helmet is a no-brainer. The CDC quotes a study by Deitmar Otte that shows that your cheeks and jaw are the most likely parts of your head to be smooshed into the road in a crash.

This in mind, the adage I prefer is: "Only use a 3/4 helmet if you got a 3/4 face, or if you currently got a 4/4 face but wouldn't mind if 1/4 of it got busted up and then you'd only got a 3/4". Doesn't roll off the tongue, but you get the idea.

Even worse than 3/4 helmets: "Skid lids" offer virtually no protection.

Think about it. You're counting on landing directly on the top of your head, with the rest of you never touching the grindtastic asphalt. Seems a little optimistic.

So helmets are pretty straightforward - buy a full-face.

Gloves are a little more complicated, but still essential for riding on or off-road - not just in case of a bad crash, but also in case you ride through some thorns or poison ivy, or you need to briefly touch a hot component of the motorcycle to lift it or shove it around. Good gloves are grippy, easy to wear and not terribly expensive given the added comfort and protection. They should fit so you can reach the levers, without extra fabric flopping around at the controls. If you ride on the road, your gloves need to be tough enough to slide down pavement without disintegrating - again, leather is ideal but padded textile works too. Hard knuckles limit force distributed to your fingers, keeping your metacarpals from fracturing. Most of my riding is in hot weather, so I like the Fox Bombers. They offer good general-purpose protection and are reasonably comfortable and durable for the price.

There are lots of styles and colors available, so go crazy.

On to boots: If you forced me to ride off-road with just one protective item, I would probably pick boots (I guess that's two items...whatever). You should have solid MX boots whether you're trailriding, ADV riding or even commuting. If your foot gets stuck between a rock or tree and the bike's footpeg, you want something that can handle the force as it's transmitted from the tree to the 400lbs+ bike/rider combo - regular hiking boots are not adequate, and sneakers are only slightly less idiotic than flip-flops.

Instead of MX boots, some ADV riders prefer variants like enduro boots, adventure boots or even street boots. To a new rider, they probably feel more flexible and comfortable than beefy MX boots, but they don't extend as far up the shin, so they're considerably less protective. Boots tend to loosen a bit during break-in, so even the stiffest MX boots are fabulously comfortable for an all-day street ride followed by a hike up to the view. Here I'm wearing O'Neal Element MX boots hidden under my Kevlar riding pants (so it doesn't look like Iron Man's day off):

So far we've discussed both abrasion and impact protection, but we haven't said anything about hyperextension. I'll be honest, I didn't think a neck brace was practical or useful for anyone except MX racers, but I bought one on a whim and it's already saved my life once.

Leatt braces are also pretty affordable (nice ones are usually under $400), very easy to fit and surprisingly comfortable - you don't even know it's there until it saves you. I used to think braces were one of those "it's not for everyone" pieces of kit - but over the past few years they have become so effective, so comfortable and so cheap, it's hard to argue against picking one up and wearing it on every ride.

Is there empirical evidence that any of this stuff actually works? Tons, or maybe I should say "tonnes" - virtually all of the most up-to-date studies are from outside the USA. The last time America had such a study was in 1981, when USC Prof. Harry Hurt put together an excellent report on causes and effective countermeasures with regards to motorcycle accidents. While Hurt's findings are interesting and arguably still relevant, efforts to fund a broader and more recent follow-up study in the USA have been unsuccessful.

But think of it this way: There are old motorcyclists, who have been riding for decades and wear all protective gear they can get their hands on. Then there are bold motorcyclists, who wear little or no gear and spend more time in the hospital than they spend riding. There are no old, bold motorcyclists. The surest way to tell a newbie apart from an informed biker is whether they wear the right gear for the riding they do.

I have an uncommon vantage point in motorcycling: On the one hand, I've been riding for several years, I perform virtually all my own maintenance, and I continually strive to improve my riding skills and techniques. However, I still remember vividly what it was like to be a newbie - I'm still in touch with my new rider side.

So now is a good time to introduce what I wish I knew when I was a new rider. And the way I'd like to frame this discussion, which should span several posts, starts with a general rule:

So now is a good time to introduce what I wish I knew when I was a new rider. And the way I'd like to frame this discussion, which should span several posts, starts with a general rule:

Every bike is a set of compromises.

The people who design motorcycles know what they're doing. Every bike is the best bike in the world at being itself, and riding the way it was meant to be ridden. If you change something about that vehicle to make it better in one area, you necessarily make it worse somewhere else. An example is speed vs. comfort:

You add a little horsepower, but you also produce more noise and emissions. You take a little weight off the front, but now you have no wind protection and you're covered in bugs by the time you clear the intersection. This rule of thumb applies whether you're choosing a new bike or considering modifying your own.

And there are many such tradeoffs. Speed vs. reliability, cost vs. componentry, utility vs. sexiness...and the list goes on. Point is, there's no best bike, and there's no worst. There can only be the bike that is best for the kind of riding that you do.

So, never ask "What is the best dirt bike for racing?" or "What is the fastest street bike I can afford?" Instead, ask yourself the following questions:

So, never ask "What is the best dirt bike for racing?" or "What is the fastest street bike I can afford?" Instead, ask yourself the following questions:

- How much am I willing to spend after buying the best safety gear available for my style of riding?

- Where and when will I have the opportunity to ride?

- How much time do I want to spend wrenching vs. riding?

- What role could motorcycling play in my life?

Think about those for a while. Keep them in mind as you take every motorcycle safety skills course you can attend, and you'll have taken the first step toward finding sublimity on two wheels.

There are riders who attend weekend track days to test their speed machines in a battle for the perfect line. Some enjoy the occasional Sunday ride on the parkway, with a buddy riding pillion. Others ride around the block, or around the world. We're going to do a little bit of all of that in the coming blog posts and galleries. I look forward to telling you all about it, and maybe even seeing you out there somewhere.

Ride safely.